On a cool night this past spring, the line outside the Blue Note ran down the block, causing enough of a scene that a young man stopped to ask, “Who’s it for?” A woman in a fur coat near the front shouted back, “Eddie Palmieri!” “Ah, Eddie Palmieri,” the passerby replied, “Con razón!” The eighty-seven-year-old Nuyorican pianist and bandleader has been a fixture of the city’s night life since the nineteen-fifties. Critics have called him “our Beethoven” and “the architect of progressive salsa.” To fellow-musicians, he’s El Rumbero del Piano, Maestro, and the Latin Monk (as in Thelonious). Eddie II, Palmieri’s manager and his only son, puts it more plainly: “My dad is the No. 1 Motherfucker.” These days, Palmieri often describes himself as “the Last of the Mohicans,” having survived many of his hard-living peers.

In 2023, Palmieri was hospitalized with respiratory problems, and his doctors told him that he would never tour again. This concert, one of several sold-out shows at the Blue Note, seemed like a kind of resurrection, and I felt lucky to squeeze myself in among the crowd. When Palmieri took his place at the piano, he complained that his mike was too quiet—“Do we have an engineer, yes or no?”—but his voice, an uptown rumble, took easy command of the room. “Fine,” he said. “I’ll say hello with music.” He began to play. After a few minutes, I recognized the prelude to “Adoración,” one of his most celebrated salsas. In 1975, the scholar Robert Farris Thompson described the opening solo as “avant-garde rock, Debussy, John Cage, and Chopin”; now it conjured birds tracing figures on a dark lake. Palmieri broke the spell to shout out the beat, and his band came in with a roar. There was no singer onstage, so the trombone took on the voice’s role, and the missing lyrics began to seem like an ode to the music itself: when I’m sad and broken / you give me breath, my heart, you’ve understood me. Later, the bongocero Orlando Vega picked up his cowbell for an ad-lib, but Palmieri couldn’t resist proposing a duet, reflecting the cowbell’s pattern with hard two-note chords on the piano. “Habla!” someone shouted from the audience. “Talk that talk!”

Between numbers, Palmieri lamented the club’s tight quarters—no room for dancing—but he wouldn’t let his listeners stay slumped in their seats. He stood up to make us clap in son clave: 1-2-3 / 1-2. Most of the audience had this fundamental Afro-Caribbean rhythm on lock, but even the hesitations and mistakes intensified the moment’s liveness. In salsa, virtuosity does not require reverential quiet. For the scholar Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia, the music registers the bustle of the kitchen—“the clatter of dishes, the hiss and pop of hot oil, the conversation in front of the stove”—and the polyphony of the market, with its shouting venders. Its natural habitat is noise.

Latin music is full of directives: “oye cómo va,” “óyelo que te conviene,” “oye bien cómo es.” Listen up and listen well. Many of my first history lessons came via salsa’s dance-floor hits about Indigenous resistance, the plantation system, and the AIDS crisis. But I wanted to learn from one of the music’s original makers, so I spent several months listening to Palmieri, in concert at the Blue Note, in conversation in his kitchen, and in retrospect through his vast catalogue of records and interviews. Palmieri is our most vital link between the mambo and salsa generations, a devotee of Afro-Caribbean musical traditions, and a visionary innovator across genres. He’s remixed the Beatles with cha-cha-chá, collaborated with the legendary producing duo Masters at Work, and composed the soundtrack for “Doin’ It in the Park,” a documentary about pickup basketball. He’s played live with everyone from Carlos Santana to the jazz icon Donald Harrison, and classic Palmieri tracks like “Muñeca” or “Ay Qué Rico” still dominate the dance floors of Puerto Rican family parties.

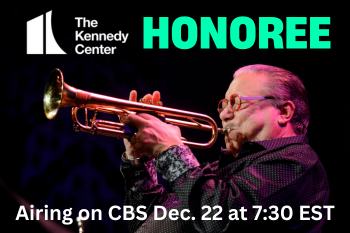

Lately, Palmieri’s been so busy that his youngest daughter, Gabriela, got him a red T-shirt quoting LL Cool J: “DON’T CALL IT A COMEBACK.” On July 18th, New York City’s public advocate proclaimed Eddie Palmieri Day, in honor of a “living legend and a trailblazer,” and he performed at Sony Hall for the occasion. In September, Palmieri played free concerts on the Boston Common and in Bryant Park. In October, Jazz at Lincoln Center inducted Palmieri into its Hall of Fame. He’s been recording new music with his band, and in a recent TV interview he winked at the possibility of a Bad Bunny collaboration (“I love carrots!”).

Palmieri can be cheeky, but he also considers himself an eternal student. His playful jam “Caminando” issues an open invitation to join this collective education: “a mi escuela yo te invito.” The story begins, he told me, with “the mighty drum,” and the African rhythmic structures that gave rise to countless genres across the Americas, from tango to ragtime. The Caribbean has long functioned as a crucial archive of ancestral practice and a major crossroads of modern musical exchange. (Jelly Roll Morton famously claimed that jazz wouldn’t be jazz without its “Spanish tinge.”) In the twentieth century, New York City became the capital of Latin music. Those displaced by the Spanish-American War and U.S. military interventions in Panama and the Dominican Republic converged on the Harlem club circuit and the nascent recording industry. Palmieri’s family had a front-row seat.

Isabel Maldonado left Ponce by steamship in 1925, and Carlos Palmieri followed her the next year, arriving in New York a generation before the city’s mid-century wave of Puerto Rican migration. Their two children were born in Spanish Harlem: Charlie in 1927, and Eddie in 1936. When Eddie was around five years old, the family moved to the South Bronx. The neighborhood was mostly German, Irish, and Jewish, and new housing projects were beginning to attract rural migrants from the Caribbean and the American South. Isabel thought piano lessons might help keep the boys off the streets. They went to study with Margaret Bonds, a Black American classical concert musician with a studio on the top floor of Carnegie Hall. But their training wasn’t only academic: Isabel’s brother had a band called El Chino y Su Alma Tropical, and sometimes the family would go down to Harlem to record 78s. In 1949, the Palmieris opened a luncheonette called El Mambo, after the Afro-Cuban music that was sweeping dance halls from Caracas to the Catskills. Palmieri told me that he remembers playing stickball out front with the radio blasting “Machito and his Afro-Cubans, Tito Puente, all day long, all night long—you had no choice!”

Mambo, as developed by the Cuban composer Arsenio Rodríguez, was a modern spin on nineteenth-century son, extending the genre’s improvised contrapuntal breaks known as montunos. New York’s version synthesized African percussion with swing harmonies, big-band brass, and the splashy solos of bebop. Palmieri often says that his favorite “bandstand warrior” on the scene was Spanish Harlem’s own Tito Puente, who showed off the rhythm section by pushing his timbales to the front of the stage. At thirteen, Palmieri became the timbalero in his uncle’s band. He dropped out of junior high and devoted himself to music, dragging his drums to gigs all over the Bronx. “I was just a wild stallion at that time,” he told me, laughing. But his mother, convinced he’d get a hernia, pressured him to switch back to his first instrument. Charlie had become a professional pianist. “Just look,” he remembers her saying. “Wherever he goes, there’s the piano.”

Piano had another advantage. When Charlie began touring, he recommended his kid brother to the bandleaders he’d left behind, including the Nuyorican bassist Johnnie Seguí and the Cuban singer Vicentico Valdés. In 1958, Eddie joined the renowned Tito Rodríguez Orchestra. Pachanga was the latest vogue: plush, Old World arrangements featuring violins and wooden flutes. But Eddie’s style had a harder edge. He was left-handed, which made him heavy on the piano’s lower notes, and he played with the force and feeling of a drummer. Later, he would even pound the keys with his palms and forearms. He told me that the first time he soloed with Valdés, the bandleader said that he “sounded like a nickelodeon”—an early jukebox—“no direction known.” But Eddie was taking direction: he was spending long afternoons with the band’s bongocero Manny Oquendo’s collection of Cuban dance records, trying to decode the structure of those lucid compositions. How did they climax so quickly, without ever seeming to rush? By listening, he was learning to compose his own music. He already knew how to use the piano as a drum, but now he began to understand it as a writerly instrument, capable of representing the whole orchestra.

In 1961, Palmieri formed his own band: La Perfecta. Oquendo came with him, and they linked up with a young Puerto Rican singer named Ismael Quintana, who had a poet’s feel for lyrics. One night, at a Bronx club called the Tritons, Palmieri heard a trombone so loud that it produced a buzzing vibration. Barry Rogers—tall, skinny, Jewish—had come up on Harlem’s late-night scene, moving fluently between jazz and pachanga, rhythm and blues and calypso. His chromatic harmonies hit Palmieri’s ear at an unfamiliar angle. Soon they were exchanging records (Miles Davis, Celia Cruz) and catching the John Coltrane Quartet live. Palmieri liked the distinctive fourth-chord voicings of Coltrane’s pianist, McCoy Tyner, and adapted them for Caribbean rhythms. This gave the music that Palmieri wrote for La Perfecta a restless feeling, as if it might go anywhere.

Together, Palmieri and Rogers deployed many elements that would influence the development of salsa: piercing trombones, sly social commentary, and the flexible structure of songs in live performance. “In every other band,” one critic wrote, “the arrangement is the law,” but, under Palmieri and Rogers, “all the guys have a voice in the way a tune is played.” In his solos, Palmieri might cite Mendelssohn, Sonny Stitt, “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” But, no matter how far he wandered, Palmieri always made sure that the whole band was locked into the beat: “As long as there’s clave,” he still likes to say, “I can do anything I want.”

Within months, La Perfecta became one of the busiest working bands in New York City. Palmieri subscribed to Tito Puente’s philosophy—“If there is no dance, there is no music”—and he was proud to make his name by filling the floor. But the ultimate proving ground, the Palladium Ballroom, remained elusive. The Palladium, on the corner of Fifty-third and Broadway, was one of the first clubs in midtown to hire Black and Latino musicians, and soon became a major showcase for Caribbean music—not just mambo but soca from the West Indies, and the folk singer Ramito from Puerto Rico. Palmieri booked La Perfecta at a spot one block down and called people in from the street. Finally, the Palladium’s owner, Maxwell Hyman, offered the upstart band a run of ninety gigs.

The Palladium welcomed thousands of patrons a week: Hollywood stars and professional performers on Wednesdays, gangsters and glamour girls on Fridays, working-class Puerto Ricans on Saturdays, and Black Americans on Sundays. La Perfecta had a special chemistry with the Sunday crowd: “Eddie, play some sugar for us!” the dancers would shout. His composition “Azúcar” tested the limits of their virtuosity with a series of rhythmic shifts, including a long, freewheeling jam that delayed the song’s climax once, twice, three times. Dancers lost hairpins and hoops in the maelstrom. In Palmieri’s piano solo, his left hand maintained a relentless montuno while his right hand invented jazzy ad-libs out of time. When La Perfecta finally released the song with Alegre Records, in 1965, it had already been a hit in the streets for two years, but listeners who’d never seen the band live assumed they’d hired a second pianist. “You had to be there to know,” Palmieri told me. At the Palladium, the musicians and dancers reached “a spiritual height that is very difficult to explain,” he said. “One time, I actually saw a man disappear—they only found the shoes.”

Not long after I went to the Blue Note, I met Palmieri at his quiet suburban home in Hackensack, New Jersey. It was raining, and Eddie II was at the door when my Uber pulled up, waiting to hustle me inside. Palmieri greeted me warmly from his seat at a table by the kitchen, and let me wander around the first floor before we settled in for our interview. I noticed a feathered plastic rooster by the stairs, Dr. Bronner’s in the bathroom, and shelves of well-worn books: Aristotle, “Earth in Upheaval,” “La Casa de Bernarda Alba.” A grand piano dominated the living room, strewn with LPs and compositions in progress. When I lifted a Bill Evans record from the bench, Palmieri spoke up: “Did you know he died at fifty-one? He was injecting himself in the fingers by that time. But he never lost his incredible touch.”

Palmieri knows how precarious life can be for many musicians: his brother Charlie died of a heart attack at sixty, and Barry Rogers died of complications from arrhythmia at fifty-five. Palmieri attributes his own longevity to “watercress, parsley, figs.” But the body can’t survive without the spirit, and “for that,” he told me, “there’s voodoo.” He was never formally initiated into any Afro-Caribbean religions, but they suffuse his music: ceremonial drum calls, protective spells, snatches of Yoruba. He feels a particular bond with the orisha Osaín, the fugitive god of the wilderness, whose shrivelled left ear is keen enough to hear the sound of a single flower crying.

Like Osaín, Palmieri has periodically retreated into a dark but fertile solitude. “Terrible years for me near the end of La Perfecta,” he told me. The band broke up for good in 1968. Big dance halls were closing. Records were eclipsing live shows. Drugs were saturating the scene. White flight was on the rise, and those who stayed were left to contend with disinvestment, redlining, and police violence. Palmieri sought refuge with Bob Bianco, a saloon singer and a vernacular philosopher who conducted Socratic dialogues in his Queens apartment. Together, they interrogated the mechanics of personal and social transformation, reading Joseph Schillinger’s theory of composition, populist economics, the history of sugar plantations in Puerto Rico. “That’s how I learned what happened and what didn’t happen,” Palmieri told me. “And then I could put it to music.”

Palmieri emerged from these sessions with a fierce critique of capitalism and a sound he called “revolt con swing.” He still felt lonely, but he wasn’t alone: by 1970, there were more than a million Puerto Ricans in New York City. Many of them were poor. Newspapers panicked over “the Puerto Rican problem,” representing migrants as unwanted and unassimilable. In his popular study of Puerto Rican ghetto life, the anthropologist Oscar Lewis infamously attributed his subjects’ desperate circumstances to a “culture of poverty.” But it was also a period of creative and political flourishing: in 1967, the actress Miriam Colón founded the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre; by 1969, the Chicago gang known as the Young Lords had reinvented itself as a revolutionary community organization and expanded its operations to New York; in 1973, Miguel Algarín and friends established the Nuyorican Poets Café. Scholars have argued that Puerto Ricans were “African-Americanized” in the city, where they developed a bluesy taste for dissonance and a talent for cultural translation. When I reached out to the great Panamanian salsero Rubén Blades, he credited Nuyoricans—Palmieri especially—with the drive “to experiment and present a position based on a different perspective and not be overly concerned with the resulting criticism.” Quintero Herencia was more blunt: “Without Nuyoricans,” he told me, “you don’t get salsa.”

Palmieri might be one of salsa’s founding fathers, but for him the term is just marketing jargon—in his words, “a lack of respect and a sin.” True practitioners know that each rhythmic pattern has a proper name and genealogy: “guaguancó, yambú, and columbia . . . and from there you have the guaracha, the son, the mambo.” Then as now, Palmieri felt responsible for sustaining these traditions. But he was also looking for ways to respond directly to the escalating crisis of his own moment.

In 1969, Palmieri released an album called “Justicia,” and the title track became an anthem for Cuban freedom fighters in Angola: “Justice they will see and justice they will get / the world and the downtrodden.” In 1971, he released the funk-fusion album “Harlem River Drive” with the sax master Ronnie Cuber and a few members of Aretha Franklin’s band: the track “Idle Hands,” an indictment of the ruling class, became the signature song of the Weather Underground. In 1977, when the Young Lords occupied the Statue of Liberty and unfurled a Puerto Rican flag beneath her crown in defense of independence activists, Palmieri held a benefit to bail them out. He played a fund-raiser for Cesar Chavez and organized concerts in prisons across New York state—Sing Sing, Attica, Rikers. His reasoning was simple: “I got friends in there.” The poet and Young Lord Felipe Luciano joined Palmieri to perform at Sing Sing in 1972, chronicling the experience for the New York Times. For him, Palmieri’s music represented “the new plan for battle, the new modus operandi for survival.”

One of Palmieri’s most famous compositions from this period is the title track of his 1971 album, “Vámonos Pa’l Monte.” The cover features a watercolor portrait of the bandleader as a depressive diasporic poet, sitting alone in a tight copse of birch trees. For the city’s exhausted workers, the song offers an escape—“a guarachar,” to party. But this isn’t the kind of getaway that lets you rest. Palmieri’s electric piano gives way to his brother’s rustic organ, as if leaving the grind of sugar works and factories behind for some secret Maroon hideout in the mountains. Sweating through the song’s seven minutes is demanding, especially once the bongocero sets off an accelerating fugue of almost shamanic intensity. Palmieri performed the song at Sing Sing, and Luciano described feeling transported somewhere high above the guard towers: “Africa, maybe? Puerto Rico before the Spaniards? Europe before the machines?” But there’s no final refuge, because the rhythm never relents, and the prisons are still full of the plantation’s children. “Every year,” Palmieri told me, “it gets worse.”

Palmieri paid a price for the revolutionary turn in his music—the F.B.I. investigated the label where he recorded—but he probably paid an even greater price for his creative independence. In 1964, the Dominican flautist Johnny Pacheco co-founded Fania Records with the Italian American lawyer Jerry Masucci, and together they began to sign talented Latin musicians: Celia Cruz, Willie Colón, Rubén Blades. “If I wanted to, I could’ve called myself Eddie Banana and the Bunch,” Palmieri quipped. He had been a defining presence at the first Fania All-Stars concert, at a West Village club, in 1968, but he was skeptical of the label’s burgeoning monopoly and the way it homogenized diverse sounds under the banner of “salsa.” He refused to sign.

In an ironic triumph, Palmieri won the first two Grammys ever awarded for Latin music, with “The Sun of Latin Music,” in 1975, and “Unfinished Masterpiece,” in 1976. But his name had already dropped out of the dominant narrative, consolidated by the Fania documentaries “SALSA” and “Our Latin Thing.” Palmieri became, according to the journalist César Miguel Rondón, “openly rebellious . . . a persona non grata.” Many of Palmieri’s compositions—“El Molestoso,” “Cuídate Compay,” “Si Echo Pa’lante”—explicitly grapple with the risks of independence, pairing complex arrangements with quarrelsome lyrics: “No creas en nadie” (“Trust no one”). Throughout the nineteen-seventies, he was exiled from the major clubs. “I was blacklisted,” he told me. “The only one who had faith in me was my wife.” Iraida passed away in 2014, and Palmieri keeps an urn with her ashes in a room off the hall. On my visit, I peeked in to see a simple altar with flowers, flickering candles, and an upright piano that she bought him on Queens Boulevard “when things were very bad,” he said. After the salsa boom of the seventies fizzled out, Iraida encouraged him to refigure his band for the Latin-jazz circuit—a pivot that probably saved his career.

Latin music has never been thoroughly institutionalized in the U.S.—it’s rarely taught at band camps, studied in conservatories, or covered by mainstream media—so its transmission often depends on the commitments of kinship. Palmieri used to send his band to listening sessions in the apartment of the record collector René López; years later, my mother would go to listening sessions hosted by Palmieri’s longtime bassist Andy González in the Bronx. Robert Farris Thompson once called these strategies “the invisible academy.” Palmieri mentors the younger players in his current band with an avuncular pride. “They’re my stimuli,” he told me. The bassist Luques Curtis is his “right- and left-hand man,” and comes around once a week to copy out new compositions. Palmieri has nurtured a striking number of now legendary artists—Lalo Rodríguez, Nicky Marrero—when they were just starting out. In 1992, Palmieri composed an album for La India, a Nuyorican freestyle singer who would become known, largely thanks to this collaboration, as the Princess of Salsa.

I was still considering kinship when I called Spike Lee; his father, Bill Lee, was a jazz musician who, like Palmieri, had played with members of Aretha Franklin’s band. In the spring, the Brooklyn-raised director invited Palmieri to perform his anthem “Puerto Rico” in a scene for “Highest 2 Lowest,” Lee’s upcoming crime thriller. “The honor isn’t his—it’s ours,” he told me. But, when I asked him about his first memories of salsa, he grew impatient. “There’s this thing called the Nuyorican,” he explained slowly. “African Americans and Nuyoricans have always lived in the same neighborhoods.” I recognized his tone from a voice-over in an old video clip of Charlie Palmieri teaching salsa in New York City public schools. “I don’t blame the United States . . . for making sure that our children don’t understand this music,” the narrator says. “Their job is to make our kids automatons, to fit their system, their aesthetic, their way of doing things.”

On my way back from Hackensack, I thought of the Caribbean Indigenous tradition known as areytos, epic narrative performances that could go on for days. “Only their songs . . . are their book or history that remains from those present to those to come,” a bemused colonizer observed in his chronicles. Juan Carlos Quintero Herencia reminded me of the sonic slippage, in Spanish, between “saborear” and “saber,” “to savor” and “to know,” suggesting the sensual dimension of knowledge, how whole mythologies can be transmitted as muscle memory. Palmieri’s compositions extend this lineage, but he maintains a wry humility about his place in the plot. “You’ve been recognized around the world,” an interviewer exclaimed, days before he was anointed a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts, in 2012. Palmieri shot back, “That’s quite extraordinary. Because I just turned the corner and nobody knew who I was!”

I came of age when salsa was in decline: the “salsa romántica” on the radio in the nineties (Marc Anthony, Frankie Ruíz) was corny and flat compared with the music of Palmieri’s generation. I called Ileana Cabra, the Puerto Rican singer known as iLe, who composed and recorded a defiant cha-cha-chá with Palmieri in 2019. She’s a millennial like me. “Lots of people underestimate salsa,” she admitted. But, for her, “la salsa de verdad, la salsa gorda” is “a super library.” Each time you press Play, she said, you have to decide “what you want to pay attention to that day . . . what’s going on with the piano, the trumpet, the mixing.” Cabra especially loves listening for traces of sweat and strain in studio recordings, like Ismael Rivera’s muffled snapping as he keeps time at the mike. I thought of Palmieri’s audible groans whenever the music heats up. He’s often said that there’s no use in trying to silence the sound of the spirit inside: “El kongo por dentro volviéndose loco.”

I went back to the Blue Note to see Palmieri two more times. I had gone my whole life satisfied by his recordings, but now it bothered me that I couldn’t catch every live show on the schedule. Salsa might be the last popular genre to emerge from spontaneous collaboration among musicians and dancers. It can’t be an accident that in Spanish you “touch” rather than “play” your instrument, skin to skin. These days, Palmieri wears gloves to keep the blood flowing to his fingers right up until he peels them off to perform, revealing nails carefully manicured with clear polish. “We’re gonna be here for the rest of my life,” he joked one night. “Whether the Blue Note likes it or not.” Sometimes Palmieri’s piano sounded impossibly light—lemon sugar, I thought, a cuchifrito carrousel—and sometimes it sounded world-weary, almost querulous. Riffing on the mambo classic “Picadillo,” Palmieri looked skyward to address his mentor’s ghost: “See that, Tito?”

Palmieri often strayed from the set list, compelling his bandmates to write new melodic lines on the fly. At one point, Luques Curtis was going so hard on the bass that Palmieri threatened to “give him the pink slip tonight, he’s stealing the show.” Now and then, I could pick out citations—Jimmy Bosch on trombone playing a bit of the Puerto Rican plena “Qué Bonita Bandera.” Despite Palmieri’s probable protestations, I thought of the samples in hip-hop, another Nuyorican form, and how many of his longer songs were like megamixes, “almost too much information,” as Cabra had told me. Just when I thought my mind couldn’t contain the dizzying multiplicity, Palmieri would resolve the tension with one or two easy strokes. “Agua!” someone shouted, as he forged ahead into a solo. At the next table over, an older man in a Yankees cap recognized the refrain from a ballad Palmieri had written for Iraida: “Incredible, man: he’s still doing ‘Life.’ ”