via NPR Music

Realness is a root position in The Omnichord Real Book, Meshell Ndegeocello’s expansive yet interior new album. That doesn’t make it the default. “I’ve been saying things I don’t believe,” Ndegeocello sings softly at one point, in a rueful refrain. “I’ve been doing things that just ain’t me.” The song is “Gatsby,” written and first recorded by Samora Pinderhughes, but it captures an essential idea that Ndegeocello seems keen to contemplate — that realness requires vigilance. It’s a principled stance often mistaken for a state of being.

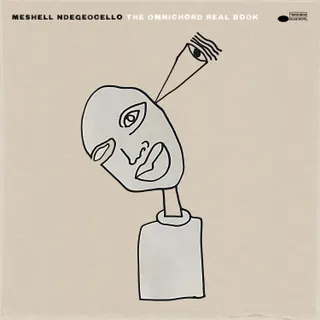

Over the 30 years since the release of her landmark debut, Ndegeocello has made truth-telling her business, along with a sound and style fed by many tributaries of Black music. The Omnichord Real Book is a coolly transfixing album — her first in five years, and her first as a leader for Blue Note. On some level it’s the product of a jarring realignment, as Ndegeocello explains in the liner notes: “Everything moved so quickly when my parents died. Changed my view of everything and myself in the blink of an eye.